Photo by civic engagement storyteller Mona Saidi.

Emily Litman, a lifelong Hoboken resident has always been acutely aware of food insecurity in her community. As a long-time teacher at Jersey City public schools, she always had kids who she knew weren’t eating at home.

“I grew up in Hoboken before it became the bougie place it is today. My family regularly volunteered at the Hoboken shelter which serves meals every day… I was aware that food insecurity always existed and I think a lot of people are not aware. if you’re not experiencing it, it’s not on your radar.”

In 2020, Hudson County was one of six New Jersey Counties with a food insecurity rate above the US rate (11.8%), with 12.2% for persons of all ages and 18.2% for children under 18, compared to 10.9% in 2018. And one in 12 households face food insecurity in the state of New Jersey, according to the report “Hunger and Its Solutions in New Jersey.”

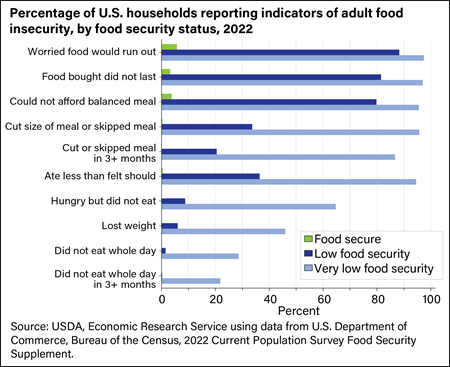

The US Department of Agriculture defines food insecurity as the lack of “access by all people at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life.” Specifically, it distinguishes between different ranges of food security (marginal and high) and food insecurity (very low and low). The USDA also makes a clear distinction between “Food Insecurity,” a “household-level economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food” and “hunger,” as “an individual-level physiological condition that may result from food insecurity.”

In early 2022, New Jersey state’s Economic Development Authority released a list of the top 50 “food deserts” in New Jersey, as directed by the Food Desert Relief Act (FDRA), signed into law by Gov. Phil Murphy in the aftermath of the Covid crisis – a law that would provide up to $40 million per year for six years in tax credits, grants, loans and technical assistance to address the food security needs of communities across New Jersey.

The list of top food deserts included six Hudson County cities: Jersey City South (the Greenville area), Union City, the North Bergen/West New York/Guttenberg region, Jersey City North (the Heights), Jersey City Central (parts of Journal Square and Bergen Section), and Bayonne, from highest to lowest food desert.

The report defines food deserts as regions which lack access to healthy and affordable food options based on 24 factors, including:

- geographic access to food (e.g. supermarket and transportation availability)

- economic factors (e.g. poverty level, unemployment rate, SNAP access etc.)

- health factors (e.g. obesity rate)

- demographics (e.g. household size, ethnicity)

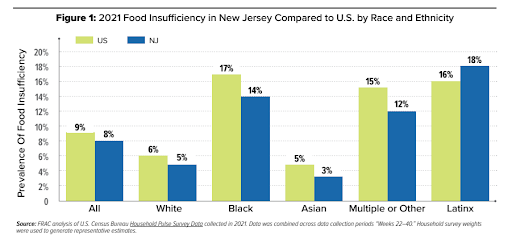

The disparities in food insecurity in the state are not only geographic, they’re also demographic, with disproportionate rates of food insecurity along racial and ethnic lines. An analysis of the Census Household Pulse Survey by the FRAC shows that in 2021, 14 percent of Black households and 18 percent of Latino households in New Jersey were affected by food insecurity compared to 5 percent of white households.

“People have this idea in their head…It’s not who you think it is that’s going to come in and ask for food. It’s sometimes well dressed people who look better off than me,” Litman said.

Refugees, asylee populations and undocumented immigrants are another population that is overwhelmingly affected by food insecurity. These communities typically have no income, limited English – which is a huge barrier in employment and in dealing with administrations – or they don’t have work authorizations (typically the case for asylum seekers and undocumented immigrants).

“Because of the crisis in 2021 and the crisis in Syria in 2017, most of our families are muslim. However, because of the political climate, we are now receiving Spanish-speaking people from South and Central America,” said Kenna Mateos, Director of Programs at Welcome Home Jersey City.

“Because our families have such limited financial literacy, they go through their SNAP or WIC benefits very quickly.”

Welcome Home Jersey City is a local non-profit that provides wrap-around social services to refugees, asylee populations and undocumented immigrants such as food access, administrative support, clothing donations, employment and education support, etc.

The food system is a complex landscape made up of many sectors and actors which impact food insecurity. The report “Hunger and Its Solutions in New Jersey,” which offers a comprehensive look at the issue of food insecurity in New Jersey, groups these sectors into four broad categories, each containing various initiatives which aren’t always well coordinated.

- Food supply chain (Farmers & Ranchers, Food Processing & Wholesale, Transportation, etc.)

- Food programs (Federal food & nutrition programs, Emergency food assistance)

- Consumers (Individuals, Healthcare, Schools, etc.)

- Influencers (Nonprofits & Philanthropy, Government, Food financing, etc.)

Federal nutrition programs like Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP); Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); School meal programs and Senior Meal delivery services represent an important source of support and have shown well documented positive outcomes, such as alleviating food insecurity, improving dietary intake and nutrition, reducing poverty, boosting learning and academic achievement; these benefits have a positive impact on the local economy and actors across the entire food chain.

But these programs fail to provide adequate coverage, with gaps in access and participation. An 81% participation rate in 2018 ranked New Jersey 28 of all the states. In 2020, 300,000 low-income people were left unserved, leaving out eligible participants and unused federal money on the table. The top identified barriers were lacking customer service, a cumbersome application process and income limits that left out many locals in need.

“Social services are very helpful; when they work well, they work well,” Mateos added. “We have a dense population of refugees and immigrants. I think they do their best, but even English speakers have trouble accessing their services. I’m sure social services are swamped and probably understaffed.”

The emergency food sector remains a key source of support for addressing immediate food needs and other basic necessities (clothing, toiletries, transportation, etc). There are numerous community-based efforts–usually funded by philanthropic donations, private donations, and food industry donations–that were born out of a desire to help the community, especially in the aftermath of the pandemic. These initiatives include food banks, mobile pantries, community fridges and food recovery programs.

“The services that are really helpful are the community grassroots organizations and nonprofits, Mateos said. “Organizations like the Food pantries (St. Peters’, Triangle Park), the Clothing Closet, and Headstart are so helpful and so easy and it really takes the load and responsibility off of us. We try to connect our clients to these high quality food services.”

One of those programs is Saint Peter’s Campus kitchen, a local food pantry run by Saint Peter’s University, which recovers food from local kitchens to serve the local community in Bayonne and Union City. Every day, the kitchen delivers dinner to various organizations, including individuals, veterans and womens’ and children’s shelters and safe houses. The kitchen is largely run by volunteers and student leaders. In addition to delivering food, Saint Peter’s is open twice a month for people to shop for clothes, house items, toiletries and non-perishable foods.

“People are more aware of the importance of preventing food waste,” Erich Sekel, the Director of Community Service at Saint Peter’s said. “The corporate cafeterias that we recover from, because they’re intentional about it, are preventing food wasted. In nine years, we have recovered 155,000 pounds of food that would have ended up in the landfill.”

Litman said there are limits to what these programs can provide, both logistically and nutritionally.

“Each of these organizations can only do so much… especially with working parents who have to travel with a public bus all the way across town on specific days. It’s not easy for anybody.”

Nutritionally, she notes that many of these food supply places rely a lot on non-perishable foods.

“Logistically, it makes the most sense to distribute bags of rice and pasta that don’t go bad and are cheap and can feed a lot of people… In terms of fresh produce and vegetables, it depends on what’s donated or available from the greater food bank. Culturally, if you’re not exposed to certain foods… you don’t know how to cook it.”

She added that there is much more that can be done at the city level to address the food insecurity issue, avoid food waste, and educate kids about the issue.

“Charity is wonderful but why isn’t the city doing it? You got hungry kids, feed them. The disparity is startling,” said Litman.

“You have bags of food that are just going into the trash. If there could be a way to follow the really important health guidelines, but also make food available leftover meals, the kids would take it.”

“It’s good to educate kids about food insecurity, so if it affects them, they don’t feel so alone.”