Graphic by Edward Andilema / SOC Images.

Editor’s Note: This article contains spoilers and mentions of physical intimacy.

Years ago, I was helping move one of my friends to Waterville, Maine into his new apartment. The cable guy he’d called to install the internet was a middle-aged White man. He seemed personable enough, but also glib.

When my friend mentioned that he was originally from Harlem, the cable guy launched into a diatribe about how “infested” this historic New York City neighborhood was with crime, drugs and gang activity.

When asked the obvious question, “Have you ever been to Harlem?” He said “No.” But from the movies and TV shows he’d seen, “it doesn’t seem to be a great place.”

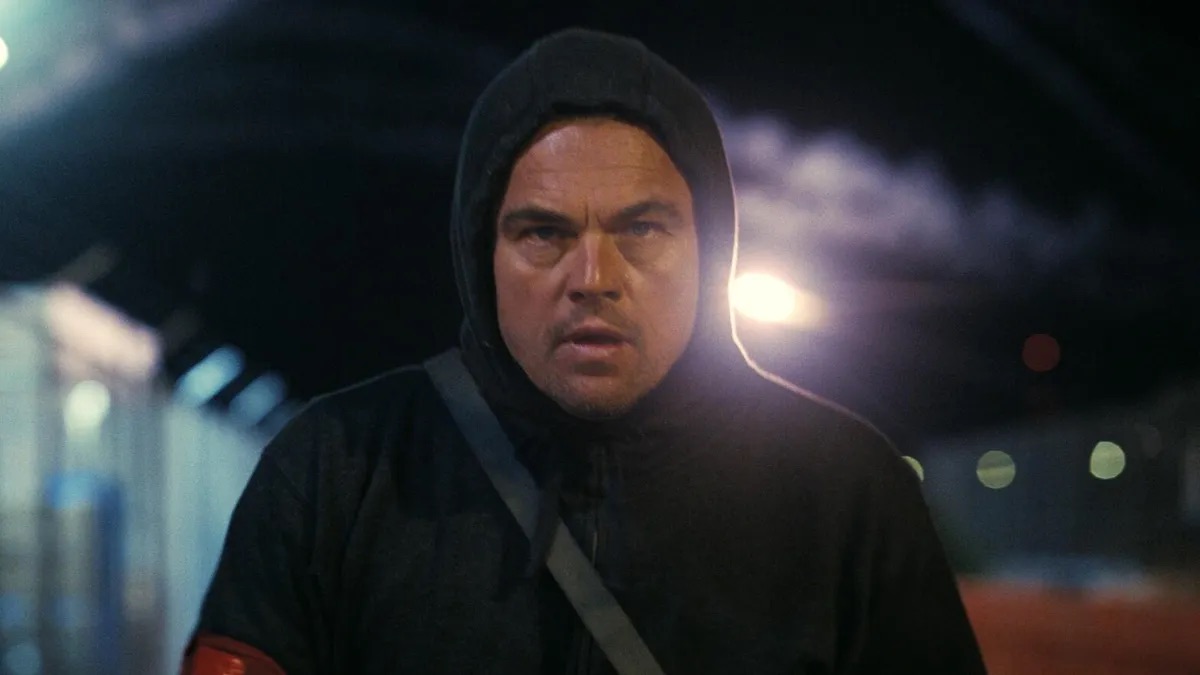

I found myself thinking about the stereotypes mentioned that day after I saw Paul Thomas Anderson’s newest film, “One Battle After Another,” starring Leonardo DiCaprio, Sean Penn, Benicio Del Toro and Teyana Taylor. I thought I was going to see a quirky, well-made film about a father’s relationship with his daughter in the absence of her mother and navigating through political rebellion. What I got instead was a movie that while technically sound, offered incoherent story choices that depict Black stereotypes through oversexualization and lack of character depth to offset it.

Penn’s character, Colonel Steven J. Lockjaw, is trying to join the Christian Adventures Club, which is a secret society consisting of far-right White supremacists. His membership is in question when the society uncovers he may have an interracial love child with a Black far-left revolutionary activist, Perfidia Beverly Hills, played by Taylor. The Secret Society must keep their bloodlines pure and, according to them, membership cannot be tainted with the race of others. With U.S. military at his disposal he invades the Sanctuary City of Baktan Cross to hunt down Willa Ferguson and Charlene Calhoun, played by Chase Infiniti, and kill her so he can regain membership of this group.

The alarming issue with this film is the characterization of Perfidia Beverly Hills.

At first, I thought this encounter would be a scene that demonstrates Perfidia using her sexuality as a weapon to advance the French 75 agenda in missions.

But that was wishful thinking on my part.

I wanted to see if Taylor and DiCaprio had any real romantic chemistry. But any interaction between them was derailed by Perfidia’s constant initiation of sex. (During one scene, she even attempts to engage in intercourse during a bombing mission).

Every other line she has, she is referring to sex. I’m not trying to be puritanical, but Taylor is not given any material that shows the thoughts of being a radical activist. In the majority of her scenes, she is strategically trying to find different ways she can mount DiCaprio.

The objectification of Taylor’s character persists in a scene where General Lockjaw perversely watches her from afar with binoculars. The camera specifically focuses on her body—a deliberate choice by the director to highlight the characters’ desirability.

But this is not the biggest misfeasance of the film.

What Anderson shows us here is that Perfidia is a Black revolutionary activist, who is a sex crazed, undisciplined, thrill seeker. She cheats on her partner and has a kid with her direct political and racial oppressor who is many years her senior. She sells out everyone she cares about to avoid prison time, leading them to be killed and or their life destroyed. She disappears and doesn’t make any attempt within 16 years to find her child again. There is nothing redeemable about this character. Not even through the electric but limited performance in which Taylor gives.

There is no nuance.

And that’s problematic given the prominent Black female character in this film is supposed to be the primary force in which we see Black activism and women in fighting against white supremacy.

Anderson reduces Perfidia to an unprincipled traitor who easily submits. This characterization would be less offensive if Anderson showed another Black woman character in direct juxtaposition of that. He has that opportunity with the underutilized, but sensational, Hall. But her character, Deandra, just doesn’t get the screentime she deserves and is rendered mostly ineffective.

In contrast, as an eccentric sensei, Del Toro’s Sergio St. Carlos shows great leadership, dedication and ingenuity in fighting the military powers to protect his community. The director has multiple scenes in which St. Carlos uses his elaborate network to help immigrants hide or escape from the military insurgency.

No Black character was given such traits in this film. Every Black character, aside from Charlene, is submitted or jailed without showing much competency in this film.

Why is that? Why go out of your way to show such a cartoonishly abysmal character like Perfidia and not highlight any other Black characters of merit and competence. It could be argued that Infiniti’s character Willa/Charlene could be that. But the character has very little interaction with other Black characters and not enough to be influenced by them.

Characters that are flawed or complex require the director to provide the audience with the character’s motivations.

For example, Penn’s Lockjaw’s motivations are villainous, but clear and shown. He is attracted to Perfidia so he stalks her and extorts her for romance. He wants to join the Christian Adventures Club so he uses his military resources to find his child and erase evidence of his parentage to gain access to the Secret Society.

With Perfidia, we’re offered no insight into her conflict or why she makes these terrible choices other than self-preservation. There is no scene that depicts Perfidia’s inner conflict with her situation and how overwhelming it may be, other than a letter to Charlene, which comes off as a poor attempt at redemption at the end of the film. But overall, given how the character is shot, the dialogue she’s given and the choices she makes, Perfidia comes off as a middle-aged White man’s interracial fantasy rather than a three-dimensional flawed human being who doesn’t comprehend the full weight of her decisions.

Anderson doesn’t show much interest in showing a complex revolutionary, but rather a parody of one.

None of this, of course, diminishes the tremendous accolades Anderson has received for his past work. Deservingly so.

And this movie is already receiving critical acclaim and talk of a possible frontrunner for “Best Picture” at the Oscars.

But it’s also poised to have a cultural impact. And consciously or unconsciously, messages and imagery in art can shape people’s views and opinions. And what a director chooses to show and not show or how they depict a group or movement can have an effect on how people view that group or movement (just ask a White guy who’s never been to Harlem).

I’m not calling for the boycott of this film. But I’m advocating for a critique of it.

Anderson has the right to make the movie he wants. It can also be argued that as talented a director he may be, he may not be the director to handle Black characters with the care they deserve.

I saw “Sinners” when it first came out. The Ryan Coogler film showed Black characters who were heroic, cowardly, selfless, selfish, jovial and depressed. Characters lost but other characters won. They were fleshed out multidimensional beings.

It is hard to find multifaceted Black women characters in popular films, let alone a complex Black woman activist. Given such a tremendous platform, an opportunity to do so should be handled with care.

Unfortunately, with “One Battle After Another,” Anderson used the opportunity and his talents to depict a caricature of one.